Background

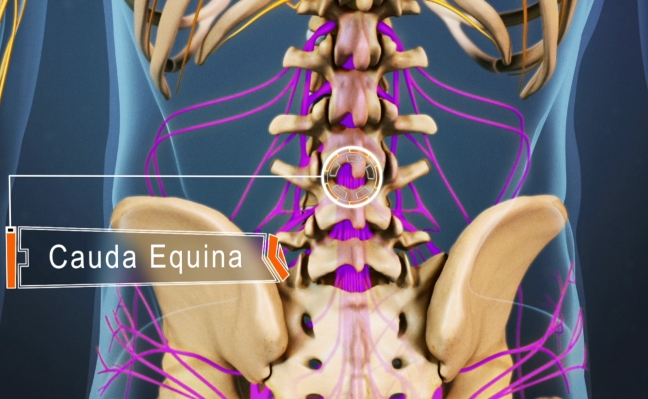

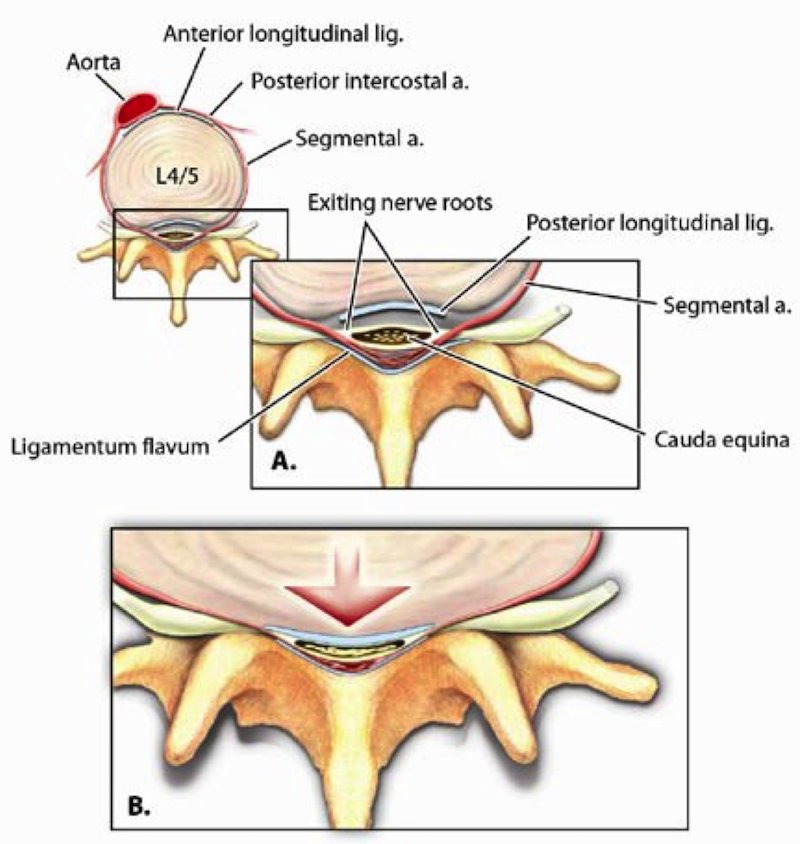

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a complex of symptoms and signs—low back pain, unilateral or bilateral sciatica, motor weakness of lower extremities, sensory disturbance in the saddle area and loss of visceral function resulting from compression of the cauda equina. CES occurs in approximately 2% of cases of herniated lumbar discs and is one of the few spinal surgical emergencies.

CES has been classified into incomplete CES (CES-I) and complete CES (or CES with true retention; CES-R).

In CESI, patients present with motor and sensory changes, including saddle anesthesia, but have yet to develop full retention or incontinence of either bowel or bladder.

Aetiology

- Compression: prolapsed disc (commonest, 2% of prolapsed discs), fracture, penetrating trauma,intrinsic spinal tumour, extrinsic tumour, spinal stenosis, ankylosing spondylitis, Paget’s disease

- Stretching: spondylolisthesis (slippage of one vertebra on another)

- Inflammation: in conditions such as arachnoiditis.

- Demyelination: loss of the myelin sheath in conditions such as Multiple Sclerosis.

- Toxic damage: (rare) due to spinal anaesthetics.

Presentation

Acute vs Chronic and CES-I vs CES-R (retention)

CES may present acutely or chronically (in the latter case, symptoms take a more indolent course). In both cases, the most common symptoms are severe back pain and radiculopathy (83% and 90%, respectively). This picture may be confusing, as 71% of patients have a prior history of back pain or sciatica. In acute CES back pain increases severely and suddenly, and there are sensory changes in dermatomal distribution plus motor weakness and possible urinary retention resulting in incontinence and need for catheterisation. Saddle anesthesia should immediately raise suspicion for CES.

CES presents as a combination of symptoms:

- Urinary history

- Saddle anaesthesia

- Loss of sexual function/bowel function

- Loss of power LLs

- Lumbar back pain

- Unilateral/bilateral sciatica

Lower motor neuron lesions of cauda equina will interrupt the nerves forming the bladder reflex arcs. The chronicity of symptoms can often mask both history and examination findings and if there is any concern an MRI should be sought.

Examination

Careful examination is key. A neurotip or needle should be used to assess sensation. This is because pin prick sensation (spinothalamic tract) is more prognostic than posterior column function due to the proximity of the spinothalamic tract to the corticospinal tract. There is 85% chance of recovery from 0 to at least 3 motor if pin prick sensation is intact in acute phase (Poynton 1997 JBJS).

- Anal tone and perineal sensation (S2-4)

- Neurological exam: Power / Sensation

- Absent / reduced Reflexes, Sciatica on SLR

- Bladder scan, catheterisation as appropriate

Investigations

- MRI is the gold standard

- Plain radiographs may give a quick indication of any degenerative changes or slips

- CT myelography should be considered in patients who cannot undergo MR

Management

CESI cases, or indeterminate cases (eg, postoperative cases), should be surgically decompressed emergently, as the neurologic and urologic outcomes are clearly improved provided the patient does not progress to CESR according to the literature. There is no clear consensus regarding the urgency of decompression for patients with CESR. However, most papers advocate early decompression, usually within 24-48hrs for all patients with CES. The actual start of this this 24-48hr clock is rather arbitrary as the onset of symptoms can be difficult to identify on a background of chronicity and delayed presentation.

- Specific history and examination

- Spinal decompression with wide laminectomy within 48 hrs (CES-I) produces good outcomes

- Early intervention in CESR

Summary

- CES produces a combination of symptoms

- Saddle anaesthesia + visceral symptoms

- MRI then surgery within 48hrs of onset recommended

- Prognosis determined by severity of symptoms

Further Reading

- Shapiro S. Medical realities of cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbardisc herniation. Spine. 2000;25(3):348-351.

- Buchner M, Schiltenwolf M: Cauda equina syndrome caused by intervertebral lumbar disk prolapse: Mid-term results of 22 patients and literature review. Orthopedics. 2002;25:727-731

- Gitelman A, Hishmeh S, Moreli et al. Cauda Equina Syndrome: A comprehensive review Am J Orthopaedic.2008;Nov:556-562

- Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, Garrett ES, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: a metaanalysisof surgical outcomes. Spine. 2000;25(12):1515-1522.

- Kohles SS, Kohles DA, Karp AP, Erlich VM, Polissar NL. Time-dependent surgical outcomes following cauda equina syndrome diagnosis: comments on a meta-analysis. Spine. 2004;29(11):1281-1287

For specific questions and interview scenarios and more links to evidence be sure to check out our sample questions and online question bank.